Thalaikoothal: the crude ritual killing of the elderly in India

/By Pastor Paul

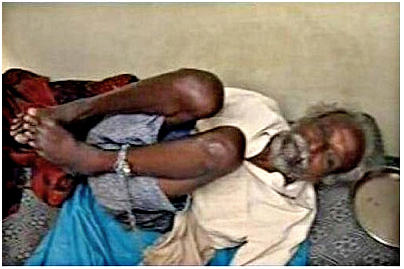

Thalaikoothal, the crude ritual practice of geronticide or involuntary euthanasia of the elderly and infirm, is still practiced in parts of India. In a sense it resembles leading a lamb to slaughter, except no knife is involved. In more than 50 villages of the districts of Virudhunagar, Mandabasalai, Madurai, Thoothukudi and Theni in the Tamil Nadu State, the favored practice involves an oil bath

Even in some regions otherwise praised for a vibrant culture encompassing all walks of life, the ritualistic practice is often accepted as an innocuous norm.

When a family is unable to bear the burden of an elderly, they kill them off. Many of the strongest hearts would cringe at the methods used.

A group of elders gather outside a village corner shop. At times thalaikoothal is practiced even with their consent

The most common practice involves first giving the person an oil bath. The body is massaged with 100 ml each of coconut, castor and sesame oils, usually at dawn. After this, the person is given a cold bath and put to bed. The body temperature soon dips, often lethally. After 15 minutes, the person is made to drink a few glasses of tender coconut water and a glass of milk. This causes renal failure. In a day or two, the person catches fever and dies.

Another method is to massage the elder’s head with cold water, causing a sudden drop in body temperature. Unable to handle the change, the individual often suffers cardiac arrest.

Should these procedures fail, a third way would be give the person a glass of mud mixed with water, or force a piece of murukku, an Indian snack, down the throat. Being difficult to swallow, suffocation and death often ensue.

Another popular method is to administer a highly-toxic tablet used to kill pigs. It costs 10 Indian rupees and is sold under various brand names, such as Quickphos and Celphos, in pesticide shops throughout the villages. The tablet is usually mixed in tea and given to the elderly. The death results from profound shock, myocarditis and multi-organ failure.

Pesticides, sleeping pills and lethal injections have also become part of it. Or, a local quack may prescribe a too-high dose of valium. A survey carried out to study the practice in Tamil Nadu reveals there could be as many as 26 different ‘acceptable’ ways to kill the elderly.

In the village of M Reddiapatti in the district of Virudhunagar, 92-year-old Subbama Veluchamy was recently ‘put to sleep’ by her family. Bedridden for more than 40 days, she had been under the care of her son and her sister-in-law’s family. One day, after a bout of diarrhoea, Subbama refused to eat or drink. This was when the family decided to give her the oil bath. However, the bath failed, and a local quack prescribed a dozen sleeping pills. These too failed to put her out of her misery. The last resort was a lethal injection. As her veins were infirm, the quack pricked her foot and took her life.

“We all could hear her crying loudly and quivering in pain. But the family cannot afford her,” said her neighbor Kasthuri.

Though villagers claim they have buried the gruesome tradition, it has now taken on a silent form. Sometimes, the elderly themselves consent to it, in which case everything will be done with full preparation. Relatives are often told the exact date, as if some marriage ceremony were to be held.

Kannaki, 65, lives with her daughter Malar on one meal a day—a cup of kanji (rice gruel) early in the morning.

“I don’t want to live," she says. "I know I will be killed as my daughter cannot afford to take care of me. But I want to die a peaceful death without pain.”

She knows her daughter has little time to take care of her. Her right leg and left hand, both paralysed, add to the burden. Malar, an agricultural laborer, ekes out a living and cannot afford her mother's medicines.

“Will you help me?” she asks her daughter, hands together in supplication. “I am a burden. I don’t want to trouble you any more.” Tears run down her wrinkled face as she lifts her head to look into the eyes of Malar. Her words are lost in sobs, and her lower lip trembles as she wipes away the tears with the corner of her muddled green sari.

Given her condition, Kannaki could soon be another victim of thalaikoothal.

As justification for the killing, some offenders say the practice enables the old to be rid of their suffering. Others say they do not have the means to take care of their parents. The truth could be anything, including ownership of property. A higher number of the elderly victims are men who usually have the property in their names, which does somewhat validate the ownership angle.

Although illegal in India, the practice has long received covert social acceptance as a form of mercy killing. The government finds itself helpless to interfere in any practice of a society fiercely divided along religious, caste and traditional lines. So no one complains and doctors often cite the reason for death as natural causes; no one is arrested for this crime. Since society accepts it as normal, there is no hue and cry. Entire villages can stand united behind those who carry out this procedure.

With the diverse ways there are now to kill the elderly, the ritual has spawned an unorganized crime sector involving middle men and quacks known as vettiar who claim to be siddhans (indigenous medical practitioners) and doctors. Because of the gravity of the act the quacks engage in, hesitatant villagers refuse to divulge more details about them. Furthermore, this happens right under the nose of law-makers and police.

Though the practice is ethically and legally unpardonable, one should note that it is sustained by the economic backwardness of this region.

“Their livelihood has always been a question mark,” says J. Manivannan of the Elders for Elders Foundation, an NGO in Cuddalore. “They are farm laborers. Both men and women work, but their daily earnings can meet only one person’s needs.”

State health secretary J. Radhakrishnan, however, claims that the government of Tamil Nadu “is doing its best for palliative care.”

That this form of murder is socially acceptable says a lot about the evil lurking in a society that appears perfectly civilized and chest-thumps about its ancient history. To the hoi polloi in the villages and towns where thalaikoothal is practiced, it is considered merely part of ‘the cycle of life’.

Even activists trying to end the barbaric tradition tread carefully. They have taken the indirect route of educating the masses about how to care better for the elderly instead of telling them outright that their practice is nothing less than demonic. Bibles for Mideast ministers in the region, attempting to end the barbaric practice by teaching the value of a soul through the love of Christ.